And Now For Something Completely Different: Some Perspective on the Transaction Fee Pilot

*** NOTE: We will be scheduling a webinar in the coming weeks to show you how transaction fees impact you without waiting for the pilot. Please contact us at learnmore@babelfishanalytics,com to reserve your spot. ***

The ramping up of the rhetoric surrounding the transaction fee pilot, from apocalyptic predictions about liquidity collapse to incendiary claims about the potential monetary impacts that hope to bring out universal pitchforks and torches, has brought both professional and armchair market structure types to proclaim that the pilot is

THE MOST IMPORTANT ISSUE FACING INVESTORS TODAY!!!

The “I see your billion dollars in liquidity destruction and raise you a billion and a half in reversion” fear-mongering is ridiculous and, quite frankly, disingenuous. Studying rebates is important and routing due to conflicts is a very real consequence, which is why we at Babelfish support a pilot. However, as long-term practitioners of transaction cost analysis and the industry’s leading experts on venue and routing analysis, we are concerned that the recent intense campaign about rebates is distorting what normally is healthy ongoing debate. We are disturbed about the way that investors are being misled by what has become a battle of marketing teams and lawyers using isolated metrics to wave the flag of “best execution”, when they are really just attempting to sell their product and in the end, potentially increase costs to the buy-side. It’s time to set the record straight on a few things.

The Only Number That Matters is the Cost to the Investor

Most of the commentary that has been put out so far has focused on metrics calculated at the individual fill level.[1] While these metrics are interesting and can be important, these are just individual data points that are taken out of context, i.e. the million share order that breaks down into thousands of individual fills. These metrics—let’s call them factors, are part of what can impact total cost. Most factors are “trade-offs”, meaning that for a higher quality fill, a trader is typically sacrificing liquidity.

For example, deciding that you want to reduce reversion (or “markouts”) by reducing interaction with so-called “toxic” counterparties by using only “clean” destinations will have the impact of potentially drastically reducing access to liquidity and may significantly reduce fill rates and velocity. If the order is passive and alphaless and you have time to wait for favorable prices, then a trading strategy that behaves in this manner is appropriate. However, if the order has both immediacy and alpha demands, know that those so-called “toxic” counterparties serve a valuable purpose and cannot be avoided. The irony is that avoidance usually results in increased parent-level costs, which is what the intention was to avoid in the first place.

The obvious point is that investment strategy should drive trading strategy, and costs should be in-line with stated objectives. All flow should be profiled and should drive your execution strategy. The maybe-not-so-obvious point is that only using so-called “investor friendly” destinations and strategies will not always result in lower overall cost. Reversion is not necessarily bad. Liquidity comes at a price and within the context of a larger strategy, you may be required to absorb reversion in order to complete the order in a more timely manner. Likewise, a trader may be willing to absorb more spread cost if it results in larger executions.

A “One Destination” Strategy Probably Isn’t Best Execution

When we come across a strategy that sources most liquidity from one or a very limited set of destinations, it usually raises a red flag. We have seen strategies that attempt to do this, from VWAPs and TWAPS, to “unique” liquidity seeking strategies that only go to single dealer platforms, or “clean” strategies that try to carve out only the “quality” liquidity. Some of these strategies are useful in the right situations, while others, such as the rebate seeking strategy mentioned in the example and some of the others further along in this paper, can be problematic.

Example:

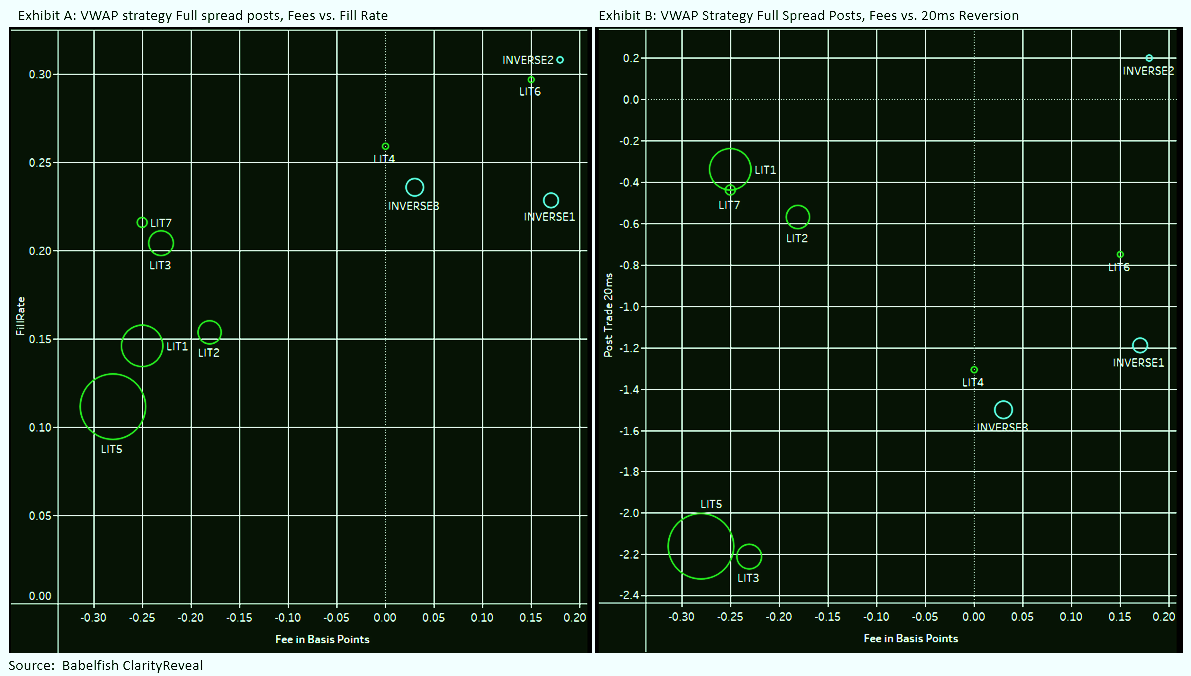

Above is a visual representation of the full-spread component of a VWAP strategy that routes to a lit destination (“LIT5”), evidencing a classic rebate-capture scheme. The largest bubble represents the most widely used destination, LIT5, which received the most routes and received the most fills. LIT5 captured a rebate of almost 30 mils. However, the fill rate for LIT5 was the lowest and the 20 millisecond reversion was extremely high. Additionally, LIT5 had a long route length (not displayed on these charts), indicating that routes were joining the queue instead of posting top of book. This resulted in price drift as the routes were waiting, and more cancelled routes. There were clearly several other destinations that received fewer routes/fills, but could have potentially yielded better performance. Ultimately, this also caused the algo to fall behind more often, resulting in the need to cross the spread. While this strategy compared favorably to VWAP, there was adverse price movement over the life of the order. In this case, the single metric is rebate capture.

Rebate Seeking or Following Liquidity?

Consider the example below where a broker posts on exchanges that offer rebates. Exhibit C[2] compares queue length on the X axis and rebate or fee (negative) on the Y axis being rebates. The bubble size represents the proportion of flow that each exchange receives. Note that almost 80% of the flow is routed to high rebate exchanges with long queues. Untrained eyes may immediately jump to the conclusion that this is a rebate seeking strategy.

In fact, the bubble sizes represent market share, making this strategy one where each exchange receives order flow in proportion to their exchange market share.

If it were a rebate seeking strategy, much of the commentary suggests that the antidote to this behavior is to begin using exchanges with shorter queues. NYSE National, with 1% of market share, has the shortest queue, followed by NYSE American, also with 1% of market share, and then IEX, with 4% of market share. While highly liquid names with low momentum may find counterparties on these destinations, it is safe to say that a trading strategy that uses fee-only exchanges that prioritize queue length as the primary source of liquidity is also a liquidity avoidance strategy with high potential for price drift.

Sometimes There Is No Line For A Reason

VWAP strategies start creating impact when liquidity is constrained and there is more risk of patterns being recognized on less liquid destinations. Hiding in a crowd is a necessary part of pattern masking and that doesn’t work as well if the crowd is thin. If the queue also takes longer to clear out (because queues at exchanges, much like queues at toll booths, do not clear out at the same pace) crossing the spread becomes a bigger part of the overall strategy. This creates impact, just like in the case of a rebate-seeking VWAP. The cost will simply be swapped from the fill level to the parent level.

This strategy is no better than one that routes half of everything to the broker’s own dark pool and in fact, will likely be worse because fills on exchanges are attributed as they happen. There is no greater signal than seeing a disproportionate share of a security being traded on a specific venue.[3] The solution for rebate seeking is not to avoid venues that offer rebates. It is dynamic routing to find liquidity were it currently resides.

We have heard arguments that some of these destinations would be smaller if rebates disappeared. Perhaps to some extent, but the size of these destinations could also be due to something completely unrelated to maker/taker incentives, such as the number of listings these exchanges house or likelihood of execution. An argument can also be made that flow that takes advantage of rebates is not necessarily the type of flow that would migrate to other market structures. We suspect that there are plenty of other incentives that exist or that will arise and market volume wars will continue. No one has a definite answer as to what happens to liquidity when rebates change or are removed—and conflicted parties talking their own book aside, we all know that the existing model needs to be revisited.

Dynamic Liquidity Sourcing, Measured by Parent Level Strategy

In the case of liquidity seeking algorithms, the ability to source liquidity should be driven in a dynamic manner, tempered by the need for immediacy (which is ultimately the alpha expectation.) This means that dynamically grabbing liquidity is somehow throttled by using different order types, sequencing, excluding, or constraining some destinations to minimize information leakage. For some algos, this may mean placing static “blocks” in an otherwise dynamic sequence—and some technologies are much more static, or completely static (sometimes for reasons that have nothing to do with liquidity seeking!) Therein lies each brokers’ proprietary advantage and certain flow and market conditions will match up better to certain types of strategies. Specific combinations of flow/momentum and diversity of portfolio managers may mean that “off the shelf” technology will never be a good fit.

While it is critical to know the complexion of destination when constructing a strategy, single statistics calculated in isolation should not be used as a central basis around which to design a trading strategy. The existence of narrow spreads, low reversion, or short queue lengths are all positive traits, but much like prescription medications advertised on TV, the list of side effects, like hair loss, flatulence, and insomnia, can be undesirable.

Just Do It

All of the commentary that we have read about the potential for Armageddon if the transaction fee does or does not happen is just conjecture as it is based on estimated data sets. Curiously, much of the speculation centers around the massive impact on the buy-side. For institutional investors, this does not have to be guesswork. The buy-side is able to know if their brokers are engaging in conflicting routing behaviors and how much it costs them. Routing data is available from every large broker and most mid-tier brokers. We produce high-quality, cost effective, routing analysis for our clients every day. Understanding whether or not brokers are engaging in detrimental rebate-seeking behavior is a decidedly knowable thing. Conversations with brokers about adjusting trading strategies to modulate this behavior is a natural follow-on. Regularly, performance improvement ensues.

A running joke in our office is that if everyone understood what their algos were doing, there wouldn’t be a need for a transaction fee pilot. Guess what? Not really a joke.

End Notes:

[1] “Individual fill level” refers to single trades. This data is typically sourced from the TAQ (trades and quotes) database, The fills sourced from this data do not include side, trading strategy, intent, type of firm behind the fill (institution, broker, HFT, etc), or any information surrounding the fill.

[2] https://medium.com/boxes-and-lines/gone-in-sixty-seconds-22094adeb0de

[3] https://mechanicalmarkets.wordpress.com/2016/01/03/pershing-square-information-leakage-on-iex/